1. Introduction to Memory Coalescing

1.1. Dynamic Random Access Memories (DRAMs)

Accessing data in the global memory is critical to the performance of a CUDA application.

In addition to tiling techniques utilizing shared memories, we discuss memory coalescing techniques to move data efficiently from global memory into shared memory and registers.

Global memory is implemented with dynamic random access memories (DRAMs). Reading one DRAM is a very slow process.

Modern DRAMs use a parallel process: Each time a location is accessed, many consecutive locations that includes the requested location are accessed.

If an application uses data from consecutive locations before moving on to other locations, the DRAMs work close to the advertised peak global memory bandwidth.

1.2. Memory Coalescing

Recall that all threads in a warp execute the same instruction.

When all threads in a warp execute a load instruction, the hardware detects whether the threads access consecutive memory locations.

The most favorable global memory access is achieved when the same instruction for all threads in a warp accesses global memory locations.

In this favorable case, the hardware coalesces all memory accesses into a consolidated access to consecutive DRAM locations.

Definition: Memory Coalescing

If, in a warp, thread $0$ accesses location $n$, thread $1$ accesses location $n + 1$, … thread $31$ accesses location $n + 31$, then all these accesses are coalesced, that is: combined into one single access.

The CUDA C Best Practices Guide gives a high priority recommendation to coalesced access to global memory.

2. Example: Vector Addition

2.1. Coalesced Access

Coalesced Memory Access means that each thread in a warp accesses consecutive memory locations so that the hardware can combine all these accesses into one single access. By doing so, fewer wasted data are transferred and the memory bandwidth is fully utilized.

Click to See Example Code

| |

Note that in NVIDIA GPUs:

- WARP is the smallest unit of execution, which contains 32 threads.

- SECTOR is the smallest unit of data that can be accessed from global memory, which is exactly 32 bytes.

In the example above, all threads in a warp access consecutive memory locations both for a, b, and c, and for each $32 * 4 / 32 = 4$ sectors, only ONE instruction to a warp is needed to access the data. This is so-called coalesced memory access.

Another example of coalesced memory access is shown below:

Click to See Example Code

| |

Crompared to the previous example, each 2 threads exchange their access positions. However, the access to memory is still coalesced.

2.2. Non-Coalesced Access

Non-Coalesced Memory Access means that some thread in a warp accesses non-consecutive memory locations so that the hardware cannot combine all these accesses into one single access. By doing so, more wasted data are transferred and the memory bandwidth is not fully utilized.

See the example code below. Originally, 32 threads in a warp would access 32 consecutive fp32 elements. However, I make the first thread in each warp access the 33th fp32 element (which should be accessed by the next warp), making an intented non-coalesced access.

Click to See Example Code

| |

The memory access pattern is shown in the figure below. Campare to the previous examples, you can see that despite the total number of load/store instructions is the same (2N/32 load instructions and 1N/32 store instructions), for each warp, 5 sectors of data are now being transferred per instruction. From the perspective of hardware, more data are being transferred than needed.

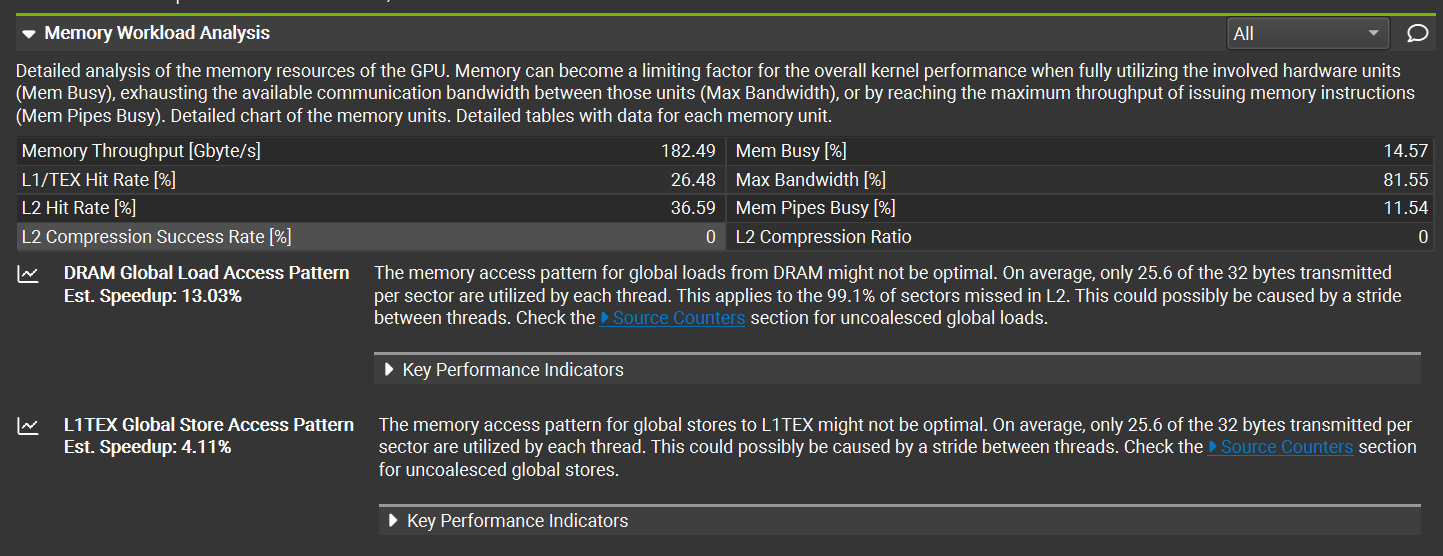

In Nsight Compute, you can see the performance analysis in the “Memory Workload Analysis” section. Optimization suggestions are provided for reducing wasted data transfer.